Overall, a rebounding economy is great news. However, if construction businesses aren’t careful, they may face more financial risk in a rebounding market than during an economic downturn. While the construction industry is starting to see positive signals of growth after the coronavirus-fueled downturn, it’s not out of the woods just yet. An economic recovery brings hidden dangers that can sink unsuspecting contractors and suppliers. This article explores some of those dangers, and what individual construction construction businesses can do to protect against the financial risks of an economic recovery or rebound.

Note: A version of this article was originally published in the CFMA’s Building Profits January/February 2014 issue. It has been revised and updated to reflect the situation on the ground in 2020.

Post-coronavirus signals point to construction rebound

The coronavirus pandemic of 2020 dealt a blow to the US and global economies. Government-imposed shutdowns drove the construction industry to a screeching halt across the country. Many construction businesses significantly scaled down operations due to the decreased market demand and uncertainty, and burned through cash reserves.

The result is an excess of contractors, property owners, and lenders that have been financially struggling during the downturn. The Association of General Contractors (AGC) reported industry job losses of 975,000 in April 2020.

However, light may be appearing at the end of the economic tunnel. As states lift stay-at-home orders and consumer confidence shows signs of increasing (albeit slowly), the U.S. economy and construction market appear staged for a rebound in mid to late 2020, and continuing over the next several years.

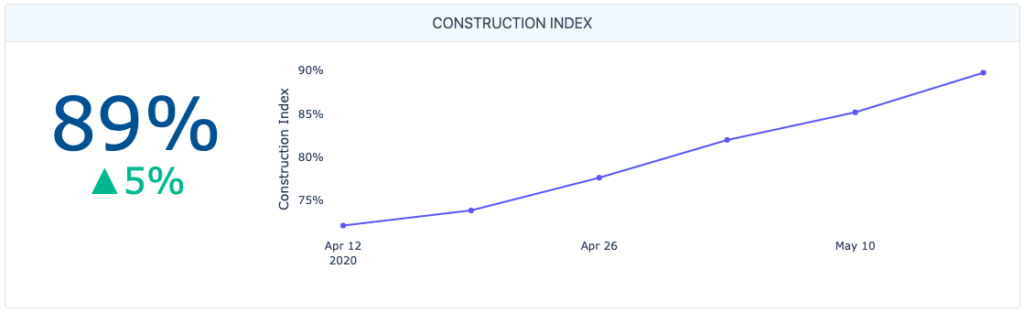

Insight from Levelset’s Construction Payment Index, which looks at state-by-state COVID-19 cases, construction stoppages, new starts, and payment disputes, shows significant recovery in the construction industry in recent weeks. The Construction Confidence Index from Associated Builders & Contractors (ABC) showed an uptick after historic lows.

Of course, tremendous uncertainty persists over the pandemic’s long-term effect, even as the economy shows signs of a rebound. Fitch Ratings expects that “the downturn in construction activity will extend into 2021,” led largely by a decrease in residential housing projects.

Construction managers should pay close attention to the signals of the inevitable recovery and adapt their business strategy accordingly. As the industry recovers, contractors and suppliers will need to take aggressive measures to protect themselves from the increased risk that a rebound will bring.

Why a rebounding economy is risky for construction

The economy’s recovery is a process, and one laced with peril, according to Thomas Schleifer, PhD, of the Del E. Webb School of Construction at Arizona State University. In a 2013 Engineering News Record article, Schleifer explained that construction companies are three times more likely to fail in a recovery than in a downturn.

Construction failure in a recovering economy? This is bad news for an industry already riddled by high business failure rates.

While it’s expected that a declining or flat economy carries financial risks, warning about an improving economy might come as a shock. Although it seems counterintuitive, a rebound economy creates a turbulent atmosphere that deserves the full attention of your credit and accounts receivable teams.

Sudden Increased Cash Needs

Unfortunately, sudden or rapid growth is a cash-eating affair. Negative cash flows are common during high growth periods and, depending on the circumstances, can persist for several years and require substantial financing.

If the post-pandemic environment does indeed lead to a rebound, it could present a host of problems for the construction industry.

Contractors will take on an increased workload and burn through cash they don’t have. At the same time, private capital sources and financing institutions are still a bit gun-shy, especially with investments in the construction sector.

In other words, contractors are starving, and they’re about to walk into an all-you-can-eat buffet. Many are going to get over-stuffed. But cash is just one problem with scaling up a previously depressed market – the task presents some practical challenges as well.

Delays & challenges in homebuilding

According to Daniel McCue, a senior researcher at Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, “the housing industry has often led the economy out of recessions.” After the 2008 recession, the homebuilding industry gave a sneak peak at the challenges in scaling a market from depressed to rebounding.

Long the scapegoat for the economic crisis, the homebuilding market took an aggressive and surprising uptick in 2013. That year, the New York Times wrote that a “sudden rise in home demand” was taking governments and builders by surprise.

By many measures, a surprise and sudden surge in construction growth is a good thing. But getting taken by surprise has its downsides. Unemployment costs and pandemic expenses have evaporated the budgets of many state and municipal governments. A sudden increase in building permit filings will greatly increase the volume of paperwork in county recording offices. This, of course, results in construction delays and adds to the cash strain.

Likewise, many laborers have moved on to other jobs or other territories. The 2013 New York Times article also reported that construction companies struggled to ramp up “because of the difficulty of finding construction workers and in obtaining permits from suddenly overwhelmed local authorities.”

An economic rebound brings everyday credit risks

The rebounding economy will present unique problems for contractors. Clearly, it may be challenging to keep up with a sudden demand for cash and output when the coronavirus-fueled downturn depleted most companies’ reserves and capacities.

Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that these problems are simply compounding the risk in an already risky market. Through the recession, many companies have built stronger credit policies and practices out of necessity. It may be tempting to sacrifice some of these practices when blinded by the allure of a marketplace full of new profitable opportunities.

This, too, however, is another reason why the rebounding economy presents financial risks. Sound credit practices are important in every shade of economy, especially so in rebounding ones.

Mitigating construction risk during an economic recovery

CFMs and credit managers are very familiar with the construction industry’s risk factors. Accordingly, preparing for the heightened financial risks of a rebounding economy won’t require foreign efforts. A construction company’s best risk management practices are the same in virtually any scenario. This makes understanding the nature and scope of the risk half the battle in succeeding against it.

The rebounding economy’s financial risks require contractors to prepare on two fronts:

- Ensuring their own financial houses are ready to handle the cash strain

- Taking precautions when contracting with others in the industry

Prepare for cash strain

Keeping one’s own house clean requires discipline and preparation. On one hand, a contractor must resist the urge to accept new business unless it has the cash to perform. Over the past few years, many companies have gotten into the habit of saying “yes” more often than “no.”

Taking on too much work may suffocate a company faster than even a pandemic ever could.

On the other hand, understanding what a company can and cannot financially handle requires the company to have a solid understanding of its finances. Accordingly, financial managers must make reliable cash flow projections and prepare for their companies’ capital needs. Conducting a recession stress test can give your team a good idea of your capacity, and help identify the weak points.

Allocate cash or secure construction financing for a best-case scenario negative cash flow run.

Secure your receivables

Security should always be a key component of a company’s financial risk plan. In the construction industry, every extension of credit should be secured by either a mechanics lien or bond claim right.

While an economic downturn has a negative impact on these rights by draining real estate equity and making sureties pinch pennies, the rebound will have the reverse effect.

In the rebounding economy, security rights should be a fitting antidote to individual business failures and cash misappropriations. Contractors and suppliers, regardless of tier, can benefit from security instruments like mechanics liens and bond claims. Mechanics lien claims are perhaps the original risk-insulating devices in the American construction industry.

Despite being more than 200 years old, these claims stand tall even today as the most effective weapon against a project’s financial risk.

Protect against subcontractor default

It will be extremely difficult to distinguish between those companies growing at a sustainable pace and those that are stretching themselves too thin. Guessing about or depending on a company’s previous track record is not reliable.

Instead, risk-shifting or risk-insulating practices can offset the risks posed by the other parties on a construction project.

Shifting financial risk in the construction contract

There is a constant financial risk shifting battle among property owners, GCs, subcontractors, and suppliers. Naturally, the financial risk associated with a construction project rests with the owner, and works its way down the contracting chain.

Shifting the risk away from one party to another begins with the contract, but the risk-shifting tug of war gets very complicated.

Current law straddles two public policy choices when interpreting any risk-shifting provision. Our country believes in the parties’ freedom to contract, empowering parties to agree to anything they want (provided it’s not against the law).

However, the U.S. also has a public policy interest in protecting those at the bottom of the contracting chain from those at the top. Mechanics lien and bond claim laws, prompt payment penalties, misappropriation of funds criminal statutes, and retainage restrictions are all examples of state governments stepping between contracting parties, determining that the financial risk of a project should be shouldered at the top of the chain, and taking steps to facilitate that result.

Property owners and GCs often craft questionable contract provisions in an attempt to circumvent this public policy. Pay-when-paid and pay-if-paid clauses are key examples of these provisions. The split in courts across the country about whether these provisions are valid risk-shifting clauses or mere “timing mechanisms” highlights the friction between these two competing interests.

In any event, the risk-shifting approach to utilize will depend on where a company falls in the contracting chain. When possible, those at the bottom should resist such risk shifting provisions as pay-when-paid clauses, pay-if-paid clauses, and even notice claim provisions. Those at the top of the chain should employ their attorneys to insert the risk shifting clauses with the best chance of surviving scrutiny (i.e., don’t get too greedy).

Reduce the risk of subcontractor default

The report from ENR’s 2013 Risk & Compliance Summit is still relevant in 2020: “The perception of risk depends on where you live on the payment chain.”

Perhaps obvious as well is that those at the top of the chain worry most about subcontractor defaults.

Property owners and GCs worry about subcontractor defaults, and even subcontractors live in fear over sub-subcontractor defaults. The risks associated with a rebounding economy only increase the importance of this threat.

The tools available to mitigate this risk are the same regardless of the economic climate: prequalify subcontractors, require performance and payment bonds, and attempt to “stay ahead” of the contractor.

Protecting your construction company in an economic rebound

It’s a sobering reality that every time a contractor or supplier steps onto a construction project, they are stepping onto a financial battlefield. The terms of the construction contract wrestle to shift the project’s risks. Payment and performance bonds are requested to insulate parties. Retainage is withheld on every payment down the chain, and parties manipulate pay applications to “stay ahead” of the other parties.

All the while, millions of dollars flow through numerous sets of hands, each hoping that this orchestra of financial chaos ends well. Mechanics lien and related security rights provide the arsenal needed in this financial risk battle.

Companies are apt to utilize these rights, which almost always require proactive action at the beginning of a contract and ongoing monitoring of each state’s specific requirements. Nevertheless, the difficulties are a small price to pay for the protections afforded by compliance.

Make smart credit decisions

Avoiding financial challenges requires assessing risk, which almost always boils down to making intelligent credit decisions. Signing a contract to furnish labor or materials to a project can impose a significant obligation upon a company, and the company owes that obligation to a customer. In construction, more than in any other industry, the quality and reliability of the customer is crucial.

While the quality and reliability of a customer may sometimes be unpredictable, it need not be secret. Many tools exist to help contractors and suppliers alike assess the risk of doing business with a potential customer, including credit checking and monitoring services, asset searches, and other services that perform business reviews and monitoring. Levelset’s Contractor Profiles, for example, provide valuable insight into a contractor’s payment performance, and their ability to avoid payment or project disputes.

There’s no silver bullet method to evaluating businesses. What’s important is that companies evaluate a potential construction customer at the onset. Making smart credit decisions doesn’t stop with a pre-contract review. If it did, most business transactions wouldn’t take place, because it’s rare to get spotless and complete credit information on a potential customer.

Instead, making a smart credit decision means evaluating the risk of a customer, and then filling in the gaps of exposure with some risk-offsetting tools, including personal guarantees, joint check agreements, credit insurance, and Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) filings.

Again, there is no silver bullet here, but companies should understand and have at their disposal as many of these tools as possible.

At the end of the day, smart decisions about taking and securing business is what will separate the companies that thrive from the companies that fail.

Conclusion: Don’t become a statistic

Everyone in construction is excited about the potential of rebounding economy, and overall, it’s great news. While getting through the rebound may be fraught with danger, it’s unanimous that the light on the other side is bright.

Clearly, however, the rebound process carries unique financial risks for those in the construction industry. Understanding and preparing for these risks will help contractors avoid becoming a fatal statistic an economic rebound.