Payment problems and delays in construction aren’t just limited to the subcontractors and suppliers on a project. Architects have trouble getting paid, too. So, how do architects get paid? And what obstacles do they face?

Let’s take a look at how and what architects are paid for their work, common architect payment hurdles — and some strategies you can use to make sure you get paid what you earned.

Deep dive: A cash flow guide for architects

What do architects get paid?

Here’s an old joke. An architect wins $10 million in the lottery. When his friend asks what he’s going to do with all that money, the architect replies, “I guess I’ll just keep practicing architecture until it’s all gone.”

Yeah, it’s even less funny when you’re an architect. But the truth is, most architects don’t make a lot of money, at least by professional standards — even though the path from entering school to becoming a licensed architect typically takes 13 years — that’s longer than becoming a doctor or a lawyer.

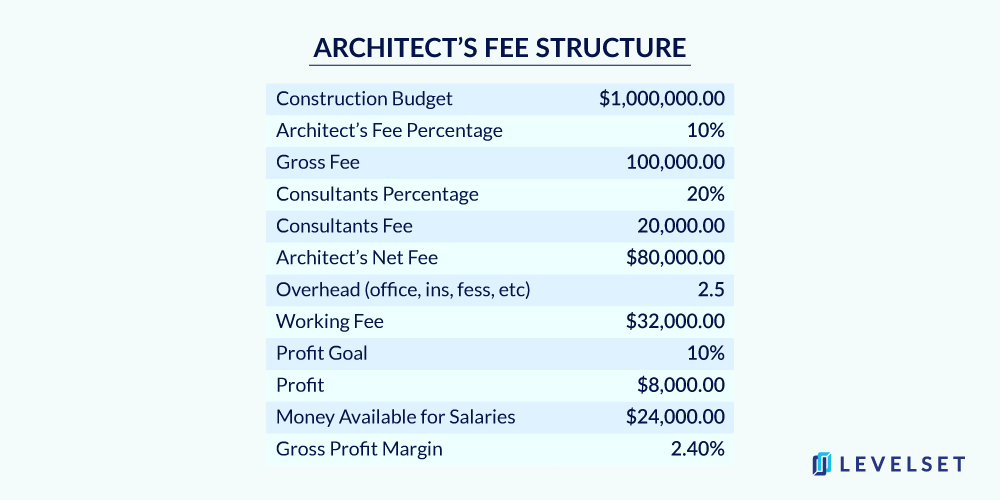

And yet, the pay doesn’t really reflect all this work. Here’s how a typical fee breaks down on a $1 million commercial building, using industry averages.

As you can see, it’s not great. Consultants’ fees for engineering, interior design, and specialty design (like commercial kitchens) can take a big bite out of the fees.

Overhead — which includes the cost of buying plenty of computing power, high-dollar drafting software, and liability insurance — is high. So, a hundred grand sounds like a fat fee…until you start parsing it out.

At the end of the day, the architect on a $1 million commercial project like this will make just a little less in salary than the realtor — who may be a terrific hard-working person, but is required to have far less training, expertise, and liability — and who has far less time involved in the project.

How do architects get paid?

Though architects sometimes work under design-build or hourly contracts, the most common method is the traditional design-bid-build process, wherein the architect and the contractor each sign independent contracts with the owner.

The architect will sign that contract, often the AIA B101, long before a contractor is on board, and the work will continue until the project is complete and the doors are opened. This work, from inception to completion, is typically broken down into five phases.

The five phases of an architect’s work

- Schematic design: The architect develops the rough sizes of spaces, the general building forms, the basic attributes, and how it sits on the site, essentially solving the problem of the building.

- Design development: This is where you finalize sizes, verify code compliance, develop systems (HVAC, plumbing, electrical, etc.), and choose materials, determining the final design of the building.

- Construction documents: The detailed drawings are prepared, telling the contractor (in excruciating detail) how to construct the building.

- Bidding and negotiation: The contractors deliver proposals and the architect, with the owner, chooses a builder and negotiates a final price.

- Construction administration: The architect represents the owner, making sure the construction documents are followed.

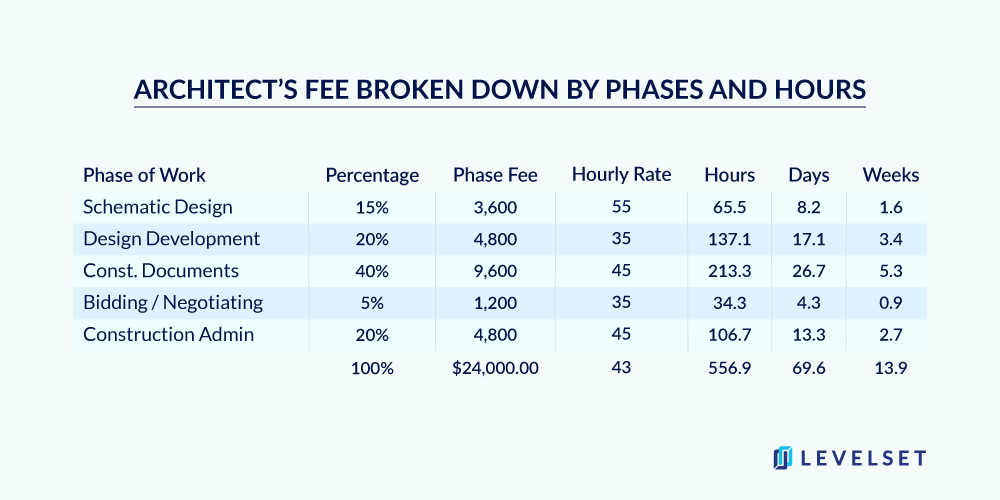

Using the $1 million building from the example above, it would look like this:

A few things to note here: First, nobody’s getting rich. The average salary shown is equal to that of a master plumber, which is a fine job, but not a path to extravagant wealth.

Also, this fee schedule demands an almost impossible efficiency. This architect has a week and a half to design the entire building. And take a look at the construction administration section: If it takes 10 months to construct the building, the architect has just 2.5 hours a week to do the inspections, have all the discussions, sort out all the issues, and do all the paperwork.

To make it even less predictable, architects don’t have regular draws, nor do they get paid upfront. On a normal project, an architect gets paid five times, once at the end of each of the five phases.

Obviously, with margins this low, it’s imperative that architects collect every penny.

6 reasons clients don’t pay their architects

Sometimes it’s as simple as an owner who has cash flow problems like everybody else. But when it’s chronic, there are usually underlying reasons.

- Bad planning: Not all clients are sophisticated business people. When they aren’t, it’s easy for them to lose sight of the relatively small portion of the big pile of money they’re spending that goes to the design. This is not helped by lending practices that are geared around construction costs and don’t always include design fees.

- Prioritizing the contractor: This happens a lot during construction administration. At the end of the project, funds can get tight and the client may decide to pay the builder at all costs to keep the project moving, knowing that delaying payment to the architect will be less destructive to the schedule.

- The relationship is too chummy: Often the relationship between the architect and client is as much social as professional. Clients tend to trust, and therefore hire, people they know. And the design process breeds familiarity and trust. But sometimes this friendly quality makes strictly business conversations harder to have and lulls a client into feeling like the business transaction is less strict than in other situations.

- The process is informal: Compared to the construction contract, with its schedule of values, prescribed pay applications, and regular pay schedule, the payment process for architects is loosey-goosey, often no more than a standard invoice sent at a seemingly random time. It doesn’t create a condition of pressure to pay quickly.

- Client’s don’t understand what you do: How many times has an architect heard this: “But the computer does the drawings, right?” No, it does not. Just as Microsoft Word doesn’t write a novel. But often clients devalue the architect’s work in this way because they don’t see it being done and don’t understand how complex and time-consuming it is.

- They get theirs first: The underlying problem for a lot of payment issues is that architects deliver the work before they get paid for it. It isn’t like a retail transaction, where in order to get what you want you have to pay on the spot. Once a client has your drawings in hand, the pressure on them to pay for the work drops.

Strategies to help architects get paid

There are some simple strategies architects can use to make sure they get paid what they’ve earned.

Pick your clients wisely

It all starts with this. Architects tend to be pleasers and problem solvers and often avoid the critical issues involved in running a successful business, like making sure the person you depend on to pay for your services will actually pay. Here are some things architects can do to vet a client.

Ask for financials and references

First of all, this sends the signal that you are operating a business. Second, it recognizes that an architect is essentially lending the client the cost of the services until they’re complete and paid for. If you were a bank lending that kind of capital, you’d check the financial health of your borrower. You can ask to see the construction loan, the line of credit, or the bank statement — anything to prove that the money they’re promising you is available to them.

If this client has built other things, call the architect who designed them. Find out if they paid on time and if they tended to waste a lot of time. Often a lovely, well-intentioned client will require so much time in extra meetings, lengthy explanations, and wishy-washy decisions, that they’ll consume your entire fee. Another architect will be able to tell you the score. Other good resources are real estate agents and contractors who have some experience with this owner.

Ask for a deposit

This is not as common as one would think, but it’s a great strategy. A standard deposit of 10%, for instance, can cover your start-up costs and provide a little cash flow upfront. More importantly, it’ll tell you who you’re dealing with. If you have trouble collecting that first check, you’ll have trouble collecting every single one of them.

Communicate expectations clearly

Your client can’t meet your expectations if they don’t know them. As the professional in the relationship, it’s your job to make things clear and to start at the very beginning.

Here are some important points to hit on.

- Remind them that cash flow is the life-blood of your business and you need it to keep the office humming and keep the work flowing.

- Point out and explain the parts of the contract that control payment, including late fees. And remind them that you’re explaining this in order to help make sure they never have to pay them.

- Stay ahead. You need to explain each step before it happens so that nobody is taken off guard. Clients mostly want to do right, you just need to give them the opportunity.

- Show your work. Clients will be happier paying for the work if they can see what they’re paying for. Be detailed in your invoices so they can see what you’ve done on their behalf. Show them your fee breakdown (like the one above) to make them understand that you aren’t pocketing a big pile of their money, but have obligations of your own to meet.

- Charge for expenses. This seems obvious, but architects are notorious for quietly absorbing expenses. Your contract will likely —and should — spell out charges for miles driven, reproductions, postage, and even some forms of project delivery. BIM (Building Information Modeling) is now often charged as an additional expense.

Be consistent

Don’t tolerate not being paid. If you accept that behavior once, it sets a precedent for every check you ask them to write.

Don’t hand over the next phase until the previous has been paid for. There is a lot of pressure to keep the project moving. But the only leverage you have is your deliverables. Sadly, you can’t do it like the old briefcase swap in a detective movie, but the closer you can get to that kind of retail transaction, the better. It’s best to at least present the invoice with the deliverables.

Don’t shy away from discussing your fees. You have to be comfortable talking about money. It is a matter-of-fact thing to pay for services, so it’s best discussed in a matter-of-fact manner. The emotions run higher when the discussion has been put off and has raised the stakes. Your fee is just another part of the process.

Collection strategies for when you aren’t paid

Sometimes, despite your best efforts, nothing works. As a young architect, I once got so desperate to collect final payment, that I went to the client’s place of business and told him I would be sitting in the showroom waiting for my money and that if anyone asked what I was doing there, I’d tell them. I sat about ten minutes before he cut me a check.

But there are better ways to collect. Here are some, in the recommended order of employ.

Call the person who writes the checks

You want to give them every chance to pay and there’s no sense in speaking to anyone who can’t deliver or authorize payment. For these kinds of calls, it’s best to try and match the position in your firm with the position in theirs. So your business affairs would call their business affairs, your manager would call their manager, and your owner would call their owner.

But if the money is significantly late, it’s often best to skip the lower-level calls and go straight to the top. In most businesses, the people at the bottom and in the middle are authorized to say “no,” but not to say “yes.”

Set late fees (and actually charge them)

Late fees and penalties are usually in your contract. If they aren’t, they should be. You needn’t make a big deal of them: You can just put them on the invoice, reference the contract, and explain that you have had to lend the project operating capital to keep it moving and that it comes at a cost.

Pause work and send notices

Letting a client know you’ve hit pause on the work is almost always enough of a motivator to get paid, because they want the work to be done. Again, keep it about the facts. You aren’t angry, but you have to pay your people for the work, and can’t do so if you aren’t paid.

You may have to send a stop notice. Check your state laws, because few actually recognize this as a legal maneuver. Also, the laws are typically written for contractors, but often apply to design professionals, too. If available, a stop notice can be very effective, because it goes beyond the client and to the lender (if there is one), freezing the construction funds until the fees are paid.

Another option is sending a preliminary lien notice. Many architects don’t know this, but in most states, architects have the right to file a professional’s lien — otherwise known as a mechanics lien or construction lien— against the property just as contractors do.

You need to check the rules in your state, but the first order of business is to file a notice that you intend to file a lien. Even if it isn’t required by law, it’s good practice — because it lets the client know that A. You have the right to file a lien, and B. You’re prepared to do it. This information can be highly motivating.

File a mechanics lien

Filing a mechanics lien is the a last resort, but a necessary one. Though liens are typically employed by contractors it is possible for design professionals to file one, encumbering the land and the improvements until payment is made.