You can be certain that somewhere in the world, lots of people are working on “payment reform” to give relief to the millions of contractors who struggle with the worst payment reality known to mankind. Construction payment is always in a state of emergency.

Don’t believe me?

In the U.K., dealing with the fallout of massive contracting group Carillion, piles of people are calling for “reform.” In the U.S., after lien legislation, prompt payment legislation, retainage legislation, and other “protections,” a new trend is emerging requiring general contractors to be directly liable for the wages of subcontractor laborers (see new California law and Maryland proposal). Major prompt payment law changes are getting passed in Canada. The “security in payments act” is beefing up in Australia.

Everywhere. Right now. Groups piled on top of groups are at each other’s throats about the balance of powers in the construction payment scheme, and regulators, who barely understand the problems, are crafting the next new schema that will help…somebody? Nobody?

This is a worldwide problem that is worsening by the day. The “law” has always failed the construction industry, and it always will.

Construction Payment Is a Mess That Is Almost Impossible To Solve

The construction industry’s payment problem revolves around money moving very slowly, and the risk of things blowing up. There’s also a bunch of practices that incentivize bad behavior (e.g. retention).

The result of this is deeply impactful.

Jobs are delayed and cost more.

Relationships are spoiled.

People struggle.

These days, there’s great progress being made by technology companies worth billions to make B2B payments better in every industry…except construction. Making construction payments better — a goldmine, by the way, $14 trillion worldwide — is an absolute black hole.

And it’s not from a lack of trying. Oracle Textura has a product that tries to help. GCPay and AvidExchange are working together trying to help. Procore has a Financials product and they’re trying to help. RedTeam, Sage, Viewpoint, etc. The list goes on and on. Great companies, and great technology products, are trying to solve this construction payment problem.

But it’s inevitable that they run into a buzz saw: the staggering complexity of the problem.

And every day — including today — damned “advocates” and regulators are doing something to make it even more complicated.

The Story Of How It Got So Messed Up

Did you know that one of the first laws known to mankind had a regulation on construction payment?!

The Code of Hammurabi dates back to 1780 B.C., back when building was simple. No technology products, no regulation, no “tiers” of parties, no banking and insurance, no complications whatsoever. Nevertheless, propped up in the middle of town on stone tablet, there it is: “ If a builder builds a house for someone and completes it, he shall give him a fee of two shekels in money for each sar of surface.”

The building industry got more complicated from there. Here are some features today:

- Building codes, sustainability requirements

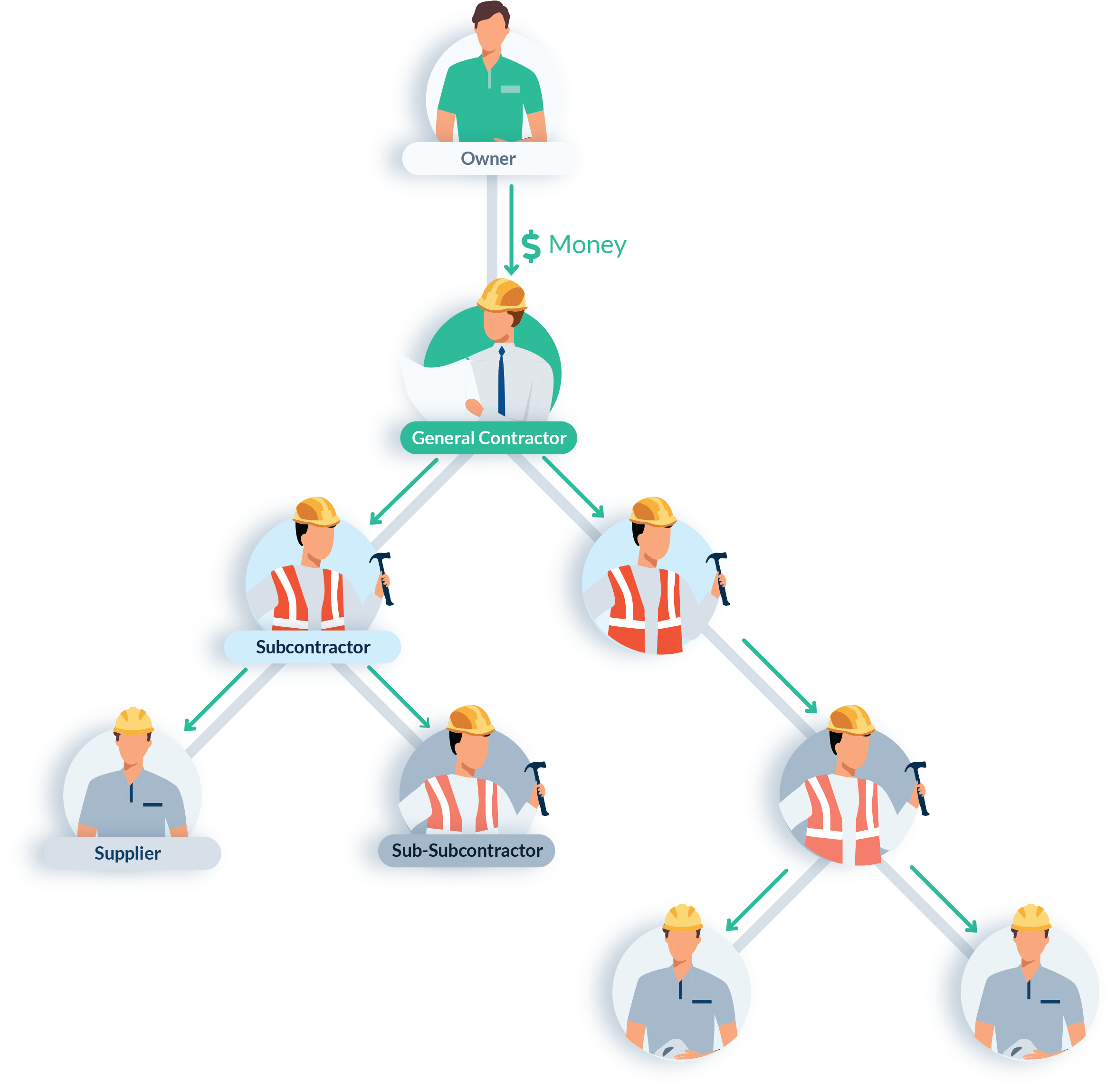

- Massive fragmentation into layers and layers of specialists

- Consolidated mega-corporations

- Insurance and bonding requirements

- Massive paperwork burdens

This didn’t happen overnight. Slowly, building things got more intricate and demanded more specialization and fragmentation. This made managing the job and managing the money, more intricate.

Since everyone benefits from getting the job completed, industry participants are mostly aligned on that outcome. Regulations aren’t as important.

When it comes to cash, however, it’s too easy for industry participants to perceive a zero-sum game. And the balance of powers between job participants is too ripe for abuse. This demanded rules.

And boy, did the industry get rules.

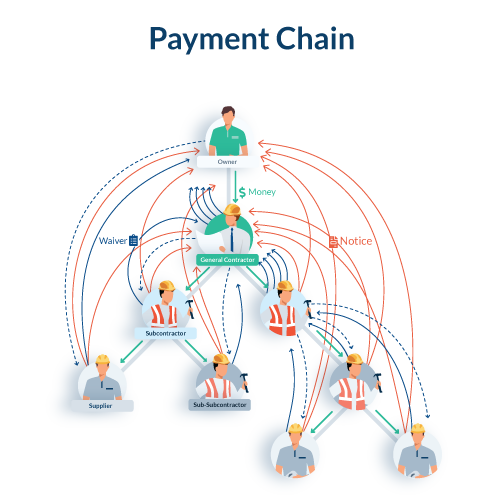

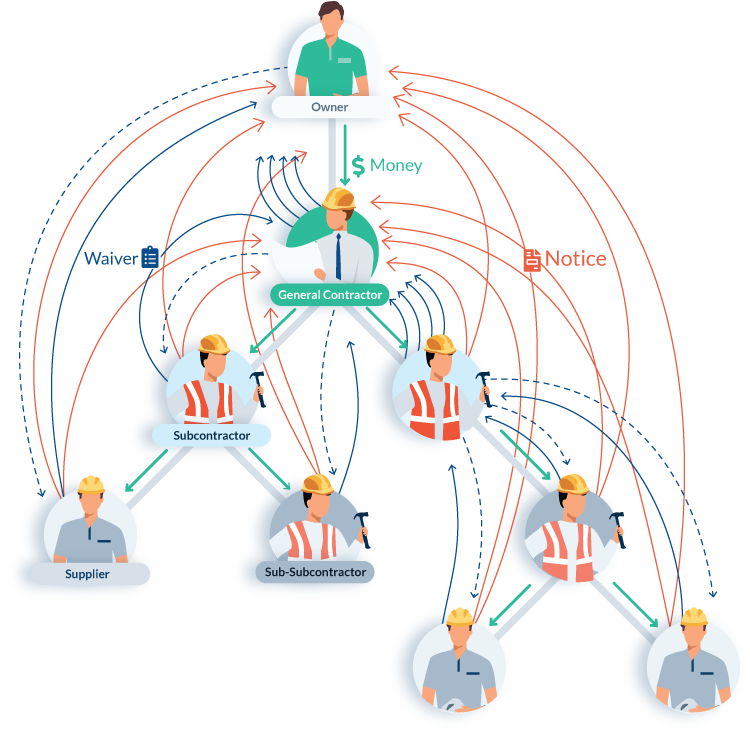

In the United States, Thomas Jefferson was among the Maryland delegates to propose the nation’s first mechanics lien laws in 1791. Literally, when passed, this became the world’s first labor laws. From then until now, in the United States and across the world, there are mountains of regulations are aimed at balancing power in the construction payment scheme. These regulations include:

- Prompt payment codes and requirements

- Retainage restrictions and frameworks

- Owner / GC liability to subs, sub-subs, and suppliers

- Lien or Claim procedures

- Notice & Waiver processes

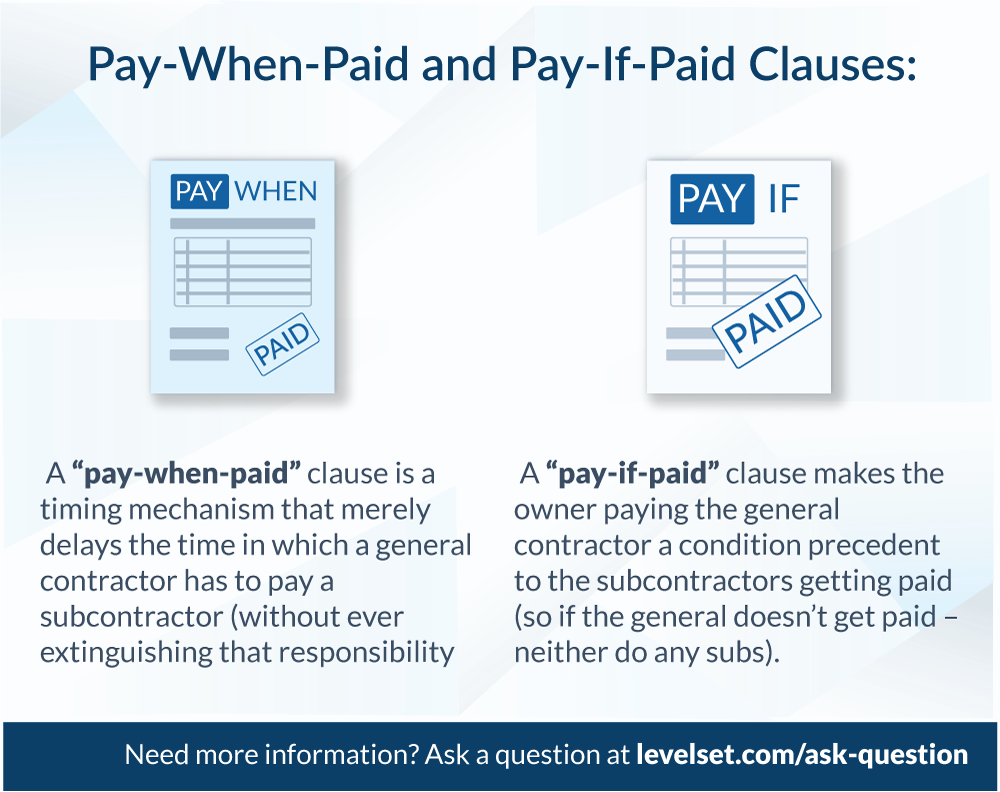

- Pay when paid and pay if paid restrictions

- And on and on and on and on

All of this stuff is changing and evolving across the world every day. Job participants set up bespoke processes and workflows to best position themselves against the others, and leverage whatever power they can grasp. Regulations impose changes to offset unfair leverage.

And every jurisdiction is completely different. It’s all so messed up.

There is so much noise.

No One’s Workflow Works

The status quo is that everyone does something to handle all of this noise. They are married to some workflow. Some crazy workflow. In most cases, because the problem requiring the workflow is so staggeringly complicated, the people mandating the workflow don’t even understand why they’re doing it. They just do it. It’s just another thing.

Do you remember the Gravitron ride from carnivals when you were a kid?

That is the payment problem in construction.

Everyone involved has good intentions and wants things to go well. Software publishers are trying to help job participants manage all of the nuances of the process. But all of the noise and complexity is just too much gravity.

Everyone’s backs are nailed to the wall and they can’t stop the noise from spawning all of the familiar problems. The slow payments. The abuse of powers.

Oh, the leverage! It tastes so good.

And so more regulation is demanded. More noise. More gravity.

Learn more about how the noise is crippling the industry:

There’s Only One Way Out

There’s only one way out for the industry.

It’s not a better way to send and manage lien waivers or to get pay applications organized or anything like that. It’s not to chase more industry regulation.

The construction industry needs to open their eyes and take a cold look at reality.

Those making payment — the lenders, owners, and general contractors — are not going to contract their way around sub-tier protections. And those getting paid — the subcontractors and suppliers — are not going to legislatively force anything. And those building software products are not ever going to catch up with all the noise.

The industry needs a dramatic shift in approach.

Out there on the Internet, nestled away on a small legal blog published by Taft Law in Cincinnati, Ohio, there’s a pithy “law bulletin” that you’d likely never find or read, written by one Joseph Cleves, Jr., titled The Paradigm Shift on Risk in Construction. “Joe” is a practicing construction lawyer. He calls out the industry, and it’s worth quoting him almost entirely:

Many owners still rely on heavy-handed contracts to provide them with risk certainty. The goal is to reduce their risk by shifting it to designers and contractors.

While this approach has a certain logical appeal, it has the paradoxical result of increasing risk instead of eliminating it. A review of case law shows that careful drafting of contracts does not provide the imagined protection…The deeply fragmented landscape of legal precedent has resulted in an environment where the outcome of disputes and impact on contract terms are unforeseeable. Rather than placing a premium on careful contract drafting, this approach renders contract drafting useless in the circumstances for which it was intended.

The search for stability calls for a dramatic change in approach — a paradigm shift. Among the possible solutions on the horizon, only an approach that eschews claims-making and litigation seems to offer the potential for success…

The construction payment process is a shared process between multiple different industries. These industries are full of good people who want the best for their business, their families, and themselves.

“Every nation has the government it deserves,” declared the French writer and diplomat Joseph de Maistre in 1811.

The problem is in the hands of the people who are suffering from the problem. Not the regulators.

Take a pause and think about the types of job participants who cause problems. You know these people exist. Just imagine how terrific it would be if you never had to do business with any of them? If you only did business with companies who had empathy for everyone on the job, who were transparent and took head-on the messy and sensitive payment processes, and who empowered everyone to work together on a foundation of clarity? Wouldn’t that be nice?

What if that was the pre-qualifier for who you did business with?

What if your prequalification process simply looked for partners who had the same world view as you, and who operated under the same reasonable methodology?

Well, it’s in your hands, isn’t it?

The status quo is not working for anyone, and it’s not going away by itself.

It’s time to shift the paradigm, from a culture of leverage and protection first — a futile attempt to achieve “risk zero”, to a culture of collaboration first.

Every Friday, we select a few articles from the week that we think are worth your time as a construction financial manager (CFM). We look for compelling articles not only about financial topics, but about business, technology, and life, that challenges you to think about your role as a CFM in different ways.

Every Friday, we select a few articles from the week that we think are worth your time as a construction financial manager (CFM). We look for compelling articles not only about financial topics, but about business, technology, and life, that challenges you to think about your role as a CFM in different ways.  It’s been 106 years since the Chicago Cubs won a World Series title — the longest championship drought of any major American sports team. Luckily for the ball club, their fortunes in the courthouse are brighter.

It’s been 106 years since the Chicago Cubs won a World Series title — the longest championship drought of any major American sports team. Luckily for the ball club, their fortunes in the courthouse are brighter.